YouTuber Nikocado Avocado’s extreme weight loss scam is not admirable – it’s an exploitation of obesity to gain engagement

US internet star Nikocado Avocado (Nicholas Perry) recently shocked the internet when he announced that he had lost 250 pounds (110 kg).

Perry had been posting mukbang content, in which he eats large amounts of food on camera while addressing the audience. Over a period of about eight years, his viewers saw him gain weight, share details of numerous alleged health complications, and clash with commenters and other YouTubers.

The kicker? He had apparently spent two years posting only pre-recorded content and secretly losing weight in the process—a feat he described as “the greatest social experiment” of his life. What can we learn from examining this moment in the content creation zeitgeist?

Anyone can create content, for any reason

The internet, and social media in particular, has made it easy and affordable for anyone to create any kind of content for platforms like YouTube, TikTok and Instagram.

The motivations for producing this content vary. While many do it for fun and connection, others are motivated by money and fame. With more than four million subscribers on his (main) YouTube channel, Perry certainly makes money.

However, monetization programs for content creation platforms reward popular content – not high-quality content, and not even necessarily real content.

YouTube’s recommendation algorithm also favors likes and comments, so content that is designed to evoke strong emotions is successful. Regardless of whether the viewers are friends, fans or haters, the advertising returns are the same.

This may explain why Perry’s videos have become increasingly bizarre and inflammatory over the course of his YouTube career (My New Diet as a Disabled Person and Jesus is Coming Soon, He Spoke to Me are two of the crazier examples).

As Perry told a podcaster in 2019:

They (the audience) like it when I’m angry, they like it when I’m crying, they like it when I’m excited.

The moral psychology of misinformation

With his video “Two Steps Ahead,” Perry reveals that he actively deceived his followers in an alleged social experiment by monitoring his viewers like “ants on an ant farm”:

Today I woke up from a very long dream (…) and had lost 250 pounds, even though yesterday people were calling me fat and sick and boring and irrelevant. Humans are the craziest creatures on the planet and yet I’ve managed to stay two steps ahead of everyone else. The joke’s on you.

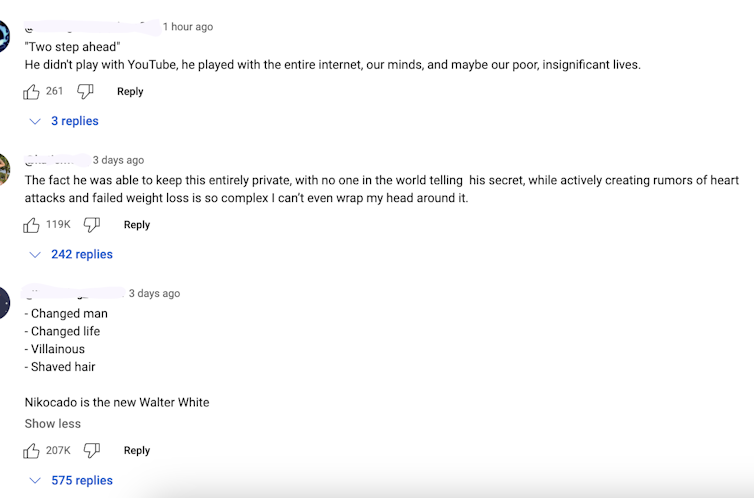

Despite his deception, the comments and resulting media coverage largely praise him for his weight loss and clever tricks.

In the age of post-truth, most people expect a certain amount of dishonesty to exist online. What’s particularly interesting, however, is that people excuse—and therefore tolerate—misinformation even when they recognize that it is false.

According to researchers, misinformation seems less unethical to us when it aligns with our own political views—and our willingness to “morally tolerate” certain untruths is why politicians can lie brazenly without damaging their image.

The fact that Perry’s deception was based on his drastic weight loss – something viewers had been pushing him to do for years – may explain why it didn’t backfire on him and his image.

YouTube/Screenshot

The ordeal is a reminder that seeing is no longer believing when it comes to the online world. Perry told NBC News:

While everyone was pointing fingers and laughing at me for overeating, I was in complete control the entire time. In reality, people are completely fascinated by internet personalities and compulsively watch their content. There is a deeper level of overconsumption in this – and that is the parallel I wanted to draw.

Jokes and speculations

Perry’s big reveal isn’t the first example of fake news designed to support a particular argument. In 2015, a journalist created elaborate but clearly fake evidence of a “chocolate diet” for weight loss, fooling news outlets and millions of people.

But such jokes often cause collateral damage while trying to prove a point. There is now speculation about how Perry lost weight. Viewers are wondering if he took weight loss drugs, and some are calling this method “cheating.”

Such discourse further exacerbates fatphobia and the false dichotomy between “fat” and “thin.”

The influence of the audience

Perry may earn good money from the thousands of comments on his videos, but they are anything but harmless.

Pick any of his mukbang videos and you’ll find plenty of disgust and “concern” in the comments. Much of it is “concern trolling,” where commenters claim to be concerned supporters when in reality they’re opponents.

Concern trolls aim to disrupt dialogue and undermine morale. Comments like “I’m just worried about your health” may sound supportive, but can be anything but.

Importantly, concerned and hateful comments are not only seen by the creators of the content. They are part of a larger discourse and also influence the way others interact with the content.

Weight stigma and aggressive comments toward overweight people remain widespread online, exacerbating the harm caused by fatphobia.

Commercialization of obesity and weight loss

Perry’s content revolves around eating large amounts of food. Such food performances can be part of fat activism and shame rejection, but they can also be part of the fetishization and commercialization of obesity and overeating.

While this content may be helpful for some people to reduce loneliness and prevent binge eating, it may lead to restrictive or uncontrolled eating for others.

In Australia, the weight loss industry was worth more than $500 million in 2023. But being on a diet isn’t just about biology or nutrition. It’s also about culture, politics and marketing.

Weight gain and loss become entertainment, and shows like The Biggest Loser reinforce obesity stigma and fatphobia while making huge profits.

In the modern age of user-generated content, Perry and other creatives no longer need a production company to exploit public interest in body-related politics for money and fame.

This story isn’t just about haters and internet fame. It’s a reflection of our collective social behavior and the changing norms around consumption, criticism, and authenticity.

While blurring the line between performance and reality to support a particular argument may have advantages, we must not forget the disadvantages.