In 2009, superstar tight end Aaron Hernandez helped the Florida Gators win the national championship. In 2012, Hernandez played in the Super Bowl for the New England Patriots and signed a contract extension worth $40 million.

But that same year, he was investigated for a double murder. A year later, he shot Alexander Bradley, one of his best friends, through the eye and murdered another man, Odin Lloyd. Two years later, Hernandez was convicted of Odin’s murder, and in 2017, Hernandez committed suicide in prison.

These are the headlines about Hernandez’s short and violent life and death, the details that not only reach diehard football fans but leave an image of him in pop culture that is hard to shake. While Hernandez clearly had drug problems, committed violent crimes and became increasingly paranoid, his full story is complicated: Hernandez was physically abused in a violent and dysfunctional home; he was sexually abused as a boy; he felt compelled by society’s constraints to hide his homosexuality; he was mauled and spat out by college football’s power brokers; and his brain was severely damaged, resulting in chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE), which likely influenced his behavior.

These nuances and much more were uncovered and outlined by the Boston Globe’s Spotlight investigative team in a series of newspaper articles and a podcast in 2018. This was followed in 2020 by a Netflix docuseries titled “Killer Inside: The Mind of Aaron Hernandez.”

1

2

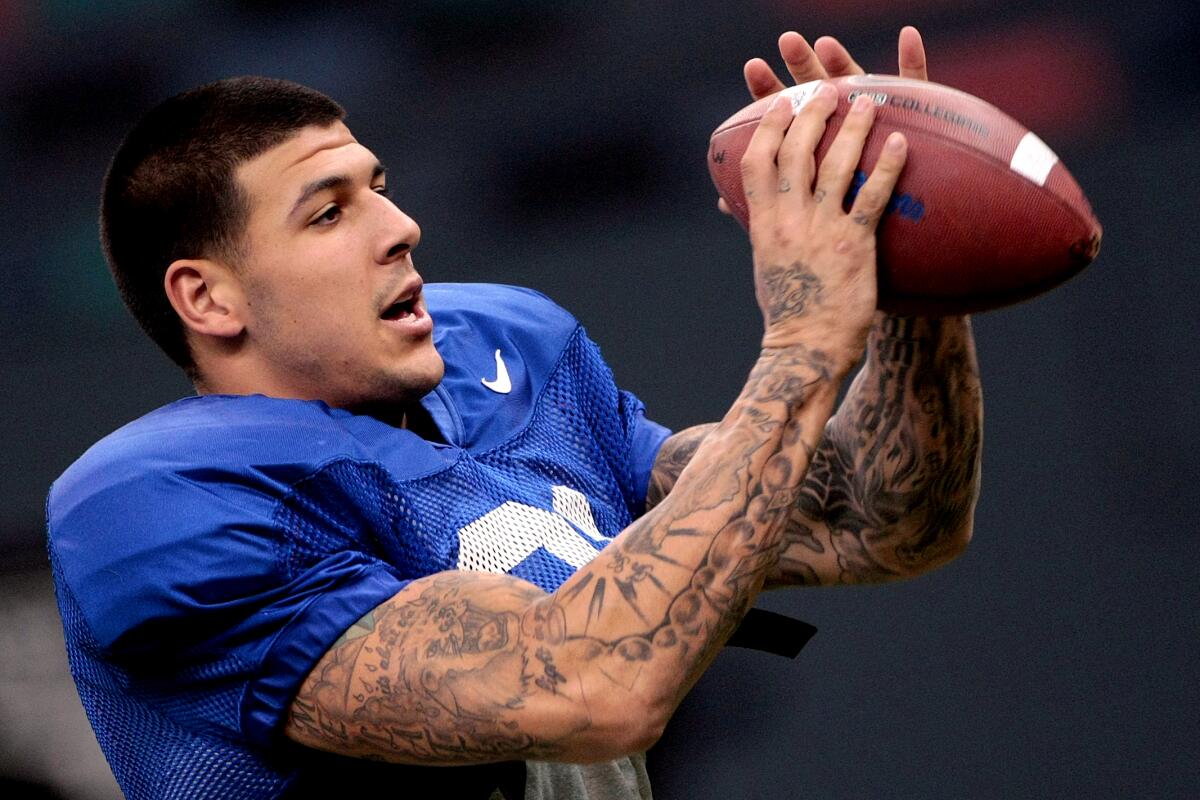

1. Aaron Hernandez in 2009 while playing for Florida. (Dave Martin/Associated Press) 2. In 2015: Hernandez during jury deliberations at his murder trial. (AP Pool)

But these days, more Americans get their news from scripted films than from newspaper series, podcasts and documentaries, whether it’s “When They See Us,” Ava DuVernay’s Netflix miniseries about the Central Park Five, or the “American Crime Story” retellings of the OJ Simpson saga and the murder of Gianni Versace. Now, the “American Crime Story” production team is expanding its options with “American Sports Story: Aaron Hernandez,” a 10-part retelling of Hernandez’s life and death based on the Globe’s reporting. The miniseries premieres Tuesday at 10 p.m. on FX with two episodes and will stream on Hulu the next day.

Brad Simpson, one of the series’ executive producers, says FX executives Nick Grad and John Landgraf tipped them off that the podcasts were about to launch and read the Globe articles.

“It had that in-depth reporting that we love to have on our shows, and we started developing the series with an eye toward making it part of our various franchises about American culture,” he says.

Simpson says his colleague Ryan Murphy, the executive producer, liked that it was a story about “a person with a fractured identity, as is the case with so many of our shows.”

The research uncovered a story that was “far more heartbreaking and complex than I had imagined,” says Nina Jacobson, another executive producer. “When you think you know a story and then you come across in-depth reporting, it really changes your perspective (and) that always makes me sit up and take notice.”

She adds that football is our national religion and that Hernandez’s rise and fall is “not just the story of one person, but a reflection of us as a country.”

Numerous writers were interested in tackling the story, but producers chose Stuart Zicherman because of his resume – Simpson calls “The Americans” – but also because he is a passionate football fan who nevertheless has the emotional distance to see the damage the game can do to people. Simpson says Zicherman provided a compelling concept for the intersection of celebrity, sport, sexuality and masculinity.

“This is about character first and football second. What sets this story apart from a million other sports stories is the story of Aaron and his family, the people on his team and the coaches,” he says. “It becomes a Shakespearean tragedy with compelling characters at the center.”

Zicherman says he brought a giant scroll with him to his first pitch that, when unrolled, revealed all the twists and turns of the story. “I love writing about stories that people think they know but really don’t,” he says. “We tend to pigeonhole people, and Hernandez was a monster, but nobody is born a monster, and I wanted to tell that story without forgiving him for what he did.”

Zicherman drew on the concept of the “American Crime Story,” which is about “taking a crime or event and making it relate much more broadly to American society.”

The show addresses toxic masculinity at home and in dressing rooms, how violence on the football field can spill over into everyday life, and how a broken family can be both a support and a trap.

Aaron Hernandez (left) in 2011 as a tight end for the New England Patriots. After his death, Hernandez was diagnosed with the degenerative brain disease “chronic traumatic encephalopathy.”

(Elise Amendola/Associated Press)

There is also the issue of CTE, the brain injury caused by repeated blows to the head. “We’re not saying that CTE made Aaron a murderer, of course – he was exposed to violence and had a tendency to be violent – but he became very paranoid and had an even more hot temper,” Zicherman says, noting that Hernandez’s drug use may also have exacerbated his brain injuries.

He lays out the story to expose the people and institutions that directly harmed Hernandez, or at least failed to “change history” for their own selfish motives. This includes then-Florida Athletic coach Urban Meyer, who seduced Hernandez and his family with promises he didn’t keep, then kicked the young man out when he became a challenge.

“We mass produce our athletes and don’t always see what’s best for them,” says Zicherman. “The Patriots were also blinded by his talent.”

“But I also want to show viewers that there is a much bigger picture at play here and that we are all a little bit to blame – we promote our athletes, pay them fortunes and make them heroes,” he says, only to turn on them when things go wrong.

Beyond the bigger picture, Zicherman focused on Hernandez’s story as someone “trying to find his true self,” giving him a throughline as Hernandez jumps from childhood to high school to Florida to the NFL and finally into the world of drugs and crime that consumed him. “He ended up going mad because of all the secrets he was keeping.”

Zicherman says the Globe’s Spotlight team not only delivered a careful and thorough story, but also had him come to Boston “to ask a million questions,” and then they visited the writers’ room to answer even more questions. “They had talked to everybody and done that work, and they were a tremendous resource,” he says.

But journalists and documentarians are limited to what they can verifiably prove. Zicherman says the series resists obvious fictionalization, but they felt it needed to go beyond the Spotlight series.

Josh Rivera as Aaron Hernandez, who was convicted of the murder of Odin Lloyd, in a scene from “American Sports Story.”

(Eric Liebowitz / FX)

“In the writers’ room, we spent a lot of time connecting the dots and emotionally exploring why things happen and finding answers to those things,” he says.

Most importantly, it was important to explain why Hernandez killed Lloyd. “It always bothered me that despite all the research, no one knew,” Zicherman says. “It was a clumsy attempt that seemed ill-considered and made no sense.”

Theories suggest that Hernandez wanted to keep his sexual orientation or his involvement in the double murder secret, but Zicherman believes it was more about how low Hernandez had sunk.

“I made up the murder from all the moments of the season,” Zicherman says. “Hernandez has so many secrets and he condenses them into drug abuse, and he’s paranoid as hell because he’s taken so many hits to the head. It’s all of it together; I don’t think it was one thing.”

Besides the scripts, the most important factor was the casting of Hernandez. And here the team got lucky. Jacobson produced “The Hunger Games: The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes” and watched Josh Rivera at work. “I could really see what he was capable of,” she says of Rivera, who had previously starred as Chino in Steven Spielberg’s “West Side Story.” “He’s an incredibly sophisticated, grounded, natural and charismatic actor. And he was that in every take.”

But although Jacobson was convinced, she also trusted Murphy’s judgment and wanted to wait for the audition “to see if he would also float to the top for Ryan.”

At the end of the callbacks, after the actors who had auditioned for different roles had been shuffled and put in relation to each other, Murphy turned around and said, “Well, it’s obviously Josh,” so they called him in again before he could leave the audition.

Zicherman says many of the other actors emphasized the violence and the darkness, but Rivera “played the vulnerability and other emotional components and the inner emotionality. Once we had him, I started cutting out the dialogue to let moments play out on his face – the other characters could talk and we could watch his grief.”

(Rivera, he adds, is also a “weirdo who likes to sing, dance and joke,” and Hernandez was the class clown before things went wrong.)

Rivera is in almost every scene. Simpson notes that he had to work out regularly to look big and endure several hours of makeup for the tattoos. “He handled it incredibly well and was always fully committed and enthusiastic,” Simpson says. “He was often exhausted, but the fact that he never drifted into a dark phase is a testament to the kind of person Josh is. He set the tone for the set.”

Simpson remembers just one day when Rivera was understandably overwhelmed by the task. “We were standing in a muddy field at 3 a.m. reenacting the murder of Odin Lloyd, and there was a moment when Josh had to stop. He turned to everyone and said, ‘This is just incredibly sad,'” Simpson says. “I think that moment haunted all of us.”